A food allergy is defined as an adverse health effect arising from an immune response to a specific food. The immune response causing a food allergy most commonly involves an antibody called immunoglobulin E (IgE), which is the allergic antibody. The IgE antibody recognizes a food allergen, and starts the process leading to an allergic reaction. Food allergy has a significant impact on quality of life, and affects social events, meal preparation, family stress, and even school attendance. Food allergy is also the most common cause of anaphylaxis, or severe allergic reaction, leading to an emergency department visit. It is therefore essential to accurately diagnose food allergies.

Even though food allergy affects 3-8% of children and approximately 3% of adults in the United States, up to 20-35% of individuals think they may be allergic to a food. Food allergy is also commonly over-diagnosed by medical providers by as much as 80%. What are the reasons for these discrepancies in the diagnosis of food allergy?

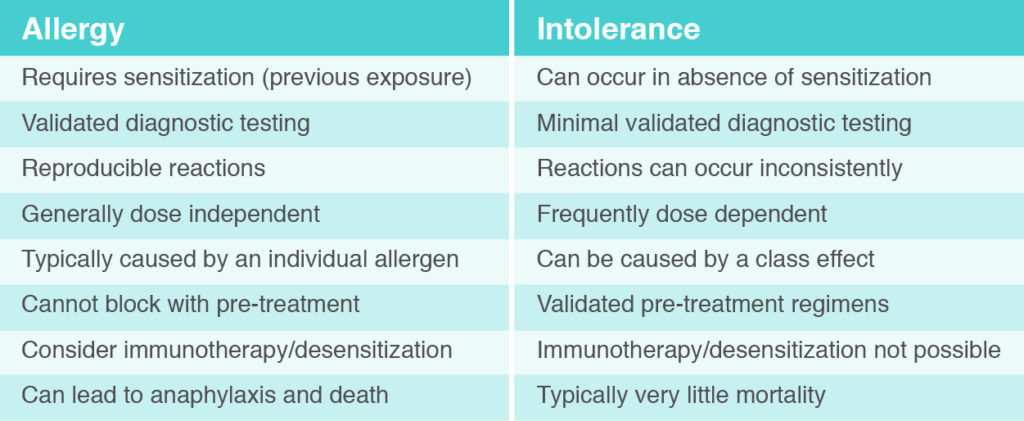

Firstly, it is important to differentiate between food allergy caused by IgE and a food intolerance or sensitivity. The attached table notes some key differences between food allergy caused by IgE versus food intolerance/sensitivity. Lactose intolerance, for example, is very different than cow’s milk allergy caused by IgE.

Secondly, misdiagnosis of food allergy also occurs because of a concept called sensitization, which is different than a food intolerance or sensitivity. Sensitization is a medical term that refers to the presence of your allergic antibody (IgE) to a food. Sensitization can be checked for with skin prick testing or blood work (frequently called specific IgE testing, RAST testing, or Immunocap). Up to 40-50% of people will have detectable IgE to food, or sensitization, but the vast majority of these people are not food allergic and can eat the food without experiencing an allergic reaction. Therefore, skin prick testing and blood work that show sensitization (the presence of the IgE antibody) do not diagnose food allergy. To have a food allergy, an individual requires both sensitization (presence of the IgE antibody) and a clinical history suggestive of reaction to a specific food. Overreliance on skin prick testing or blood work (specific IgE testing), particularly if there is no history suggestive of a reaction to the food, will therefore invariably lead to the over-diagnosis of food allergy.

Lastly, food allergy is over-reported because many food allergies resolve over time. The vast majority of children outgrow wheat and soy allergy, and most also outgrow milk and egg allergy. Even 20% of children outgrow peanut allergy. Therefore, some people think they are allergic to a food but may have outgrown the allergy over time. It is therefore important for individuals with food allergy to be periodically reevaluated by an allergist.

Since the diagnosis of food allergy can be complicated, resulting in the over-diagnosis of food allergy, what is the best approach to an accurate diagnosis of food allergy? Individuals concerned about a food allergy should be evaluated by a doctor specializing in food allergy, usually an allergist. The first and most important step in the diagnosis of food allergy is obtaining a detailed clinical history. Typical symptoms of a food allergy mediated by IgE include hives, swelling, respiratory difficulties (shortness of breath, wheezing, or coughing), nausea/vomiting, and lightheadedness/passing out (due to low blood pressure). These symptoms usually occur within 20 minutes of exposure to a food allergen, and nearly always occur within 2 hours. Symptoms not suggestive of a food allergy include chronic respiratory symptoms (such as a runny nose or asthma), frequent abdominal pain, constipation, heartburn, fatigue, headache, chronic hives, bloating, or diarrhea. If the clinical history is suggestive of food allergy, the allergist can then proceed with skin prick testing and/or blood work. Importantly, skin prick testing and blood work should not be interpreted as “positive” or “negative.” These results help determine the likelihood of a true food allergy, but are not a “yes/no” test for food allergy. For example, as the size of skin test reactivity increases (the size of the bump and redness), or as the levels of blood work increase (on a scale of 0.1 to > 100 kU/L), the likelihood of having a true food allergy increases. It is important to know that there is no definitive result on skin testing and blood work, and the results of these tests need to be interpreted based on the history provided by each patient. Additionally the size of skin test reactivity and levels of blood work do not determine the severity of an allergy. Although there is extensive research on the topic, as of today, there is no reliable way to predict the severity of a future allergic reaction. With a detailed history, followed by skin prick testing and blood work, an accurate diagnose of food allergy can be made for most individuals.

In some cases, the history, skin prick testing, and blood work will lead to an inconclusive result. For these individuals, an oral food challenge (OFC) should be performed. An OFC is a medically monitored exposure to the food, and is typically performed at an allergist’s office. An OFC is performed to confirm or refute a food allergy, or to evaluate if a person has outgrown an allergy. Generally, the food in question is given in gradually increasing amounts every 15 minutes, and the patient is monitored for signs or symptoms of an allergic reaction. When performed by an allergist familiar with the process, OFCs are safe and well tolerated, help with the accurate diagnosis of food allergy, and typically improve quality of life for people being evaluated for food allergy.

Whereas OFCs are the gold standard, or definitive test for diagnosis of food allergy, there are several tests not recommended for the proper diagnosis of food allergy. These include the following: intradermal skin testing, atopy patch testing, food IgG or IgG4testing, basophil activation testing, lymphocyte stimulation testing, applied kinesiology, hair analysis, electrodermal testing, and cytotoxic tests. Additionally, ordering “food panels” for IgE testing is also not recommended, since this reveals sensitization, but not true food allergy.

In summary, food allergy is often over-diagnosed. The most important step in making an accurate diagnosis is taking a detailed history. Skin prick testing and blood work can aid in the diagnosis, and an OFC may be required in certain cases. It is essential to accurately diagnose food allergy so patients do not unnecessarily avoid foods that they can safely consume.